Class of 2024: DNP betters quality of life for PTSD survivors

D r. Avis Simon, commander in the Nurse Corps at the Navy Medicine Readiness and Training Command at Camp Lejeune, wants to help individuals suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. She already has a plan in place designed to identify it early in military members and veterans.

Recently, she successfully defended her Doctor of Nursing Practitioner project at Georgia College & State University titled "Effectiveness of an Educational Intervention on Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Screenings for Healthcare Providers in Ambulatory Settings.”

Simon’s project addresses the screening and diagnosis of PTSD in veterans early on, which is crucial for improving their healthcare outcomes.

PTSD is a mental health problem that’s challenging for veterans and healthcare providers' ability to recognize, diagnose and successfully treat.

Simon experienced second-hand PTSD at Camp Lejeune. It spurred her interest in improving the lives of military members, veterans and their families.

“I’ve served in the Navy for 30 years,” she said. “I've been to several bases and seen PTSD in the rarest form.”

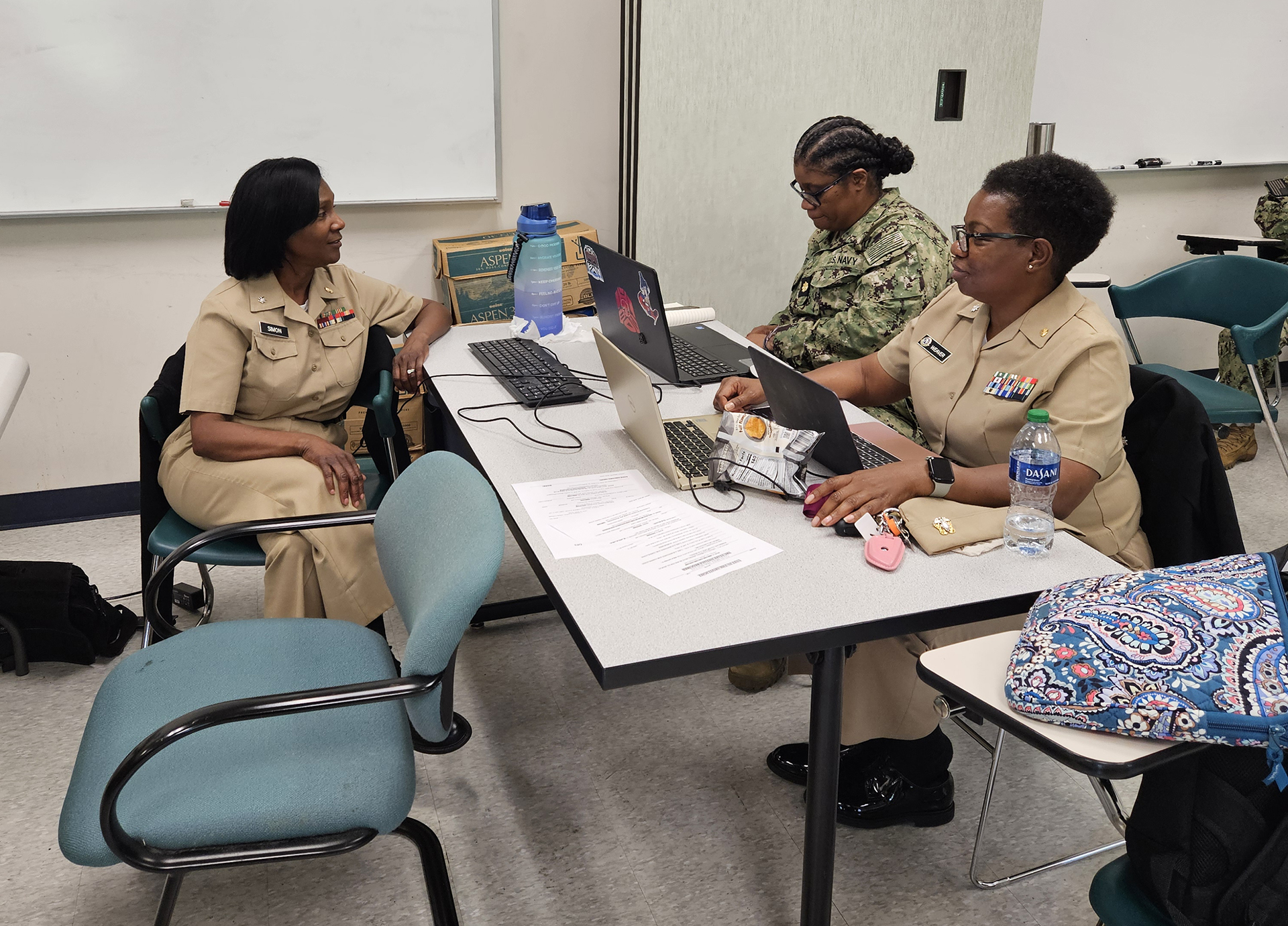

As part of her project, Simon worked with military healthcare providers, military members and veterans to get their insights on PTSD. She viewed the process at Camp Lejeune’s clinic firsthand.

Simon is passionate about diagnosing PTSD early. Her husband suffered from it when he returned home after serving in Iraq, and she saw how healthcare providers downplayed it.

“It was frightening,” she said. “I took him to the emergency room at WellStar. And they said, ‘He’s just depressed.’ So, they gave him medicine after medicine.”

Her husband continued having flashbacks.

“He kept telling me he heard gunshots,” Simon said. “He had to sleep with his rifle.”

After visiting a Veteran’s Affairs Clinic, her husband is doing much better. Getting proper care was what he needed. This experience was a lot for Simon to process.

“That opened my eyes that PTSD is real, and it’s personal for me,” she said. “I thought it would be easier to educate healthcare providers on this issue.”

This project had always been on her mind, from the moment she started pursuing her DNP in May 2021. She wanted to help educate healthcare providers on the issue.

At Georgia College, Simon enjoyed the camaraderie of learning beside her peers the most. She considers them friends and values the mentorship the program offers.

Dr. Debby MacMillan was her favorite professor because of her thoughtfulness and encouragement.

“Dr. MacMillan and I both lost our moms in January within one week of each other,” Simon said. “I wanted to stop going to school. But she kept encouraging me as I went through a grieving process. She took the time to check on me and considers others before herself—that speaks volumes of her character.”

MacMillan modeled how to be a servant leader—something Simon hopes to emulate in her profession.

“She taught me how to really care for others, investing so much compassion and time in me and kept helping me with my project,” Simon said. “She texted frequently just to check on me.”

In May 2023, Simon put her Georgia College project to work with healthcare providers on base. Her project of educational intervention on PTSD screenings for healthcare providers in ambulatory settings concluded in July.

Last summer, an Army veteran came to a military base and said he was hearing voices. He was turned away from getting the care he needed. Later, he killed four people, then was shot himself.

“Did we even bother to screen him? The answer is no,” Simon said. “We didn't take the time to do our due diligence.”

This tragedy makes Simon work even harder to help those she can. Even though there are protocols in place, she knows there are military nurses and medical doctors who don’t know how to diagnose PTSD.

“It’s up to me to educate them on how to use these screening tools,” Simon said. “Early intervention of PTSD is crucial to get our clients the appropriate care and medical referrals they need.”

Much of the U.S. population is homeless due to PTSD, Simon said. Sometimes even a vet’s family can’t be bothered with them. They return home from war—sometimes broken and wounded—and find they have nowhere to go. That isn’t good enough for Simon. She believes vets deserve better after serving their country.

“It's my sincere hope that people with PTSD get the care and treatment they need to live productive, normal lives,” Simon said. “I also want to keep them off the streets by making sure they know about the resources available to them and to let them know that there’s no fear in reporting PTSD.”

Now, armed with her doctorate, Simon plans to implement her project in her field. She’d like to teach in a nursing school.

In the meantime, PTSD often continues to go unreported. Too many are afraid, uncertain how the diagnosis will impact their military careers. They’re afraid of being judged.

“Even in the civilian world, many veterans won’t say anything when they get screened after returning from overseas,” Simon said. “You have so many people saying, ‘I'm okay.’ But my husband was not okay. If we can meet people halfway, by giving them a safe environment, they’ll feel they can report it.”