Pesticide On Your Plate: GCSU scientist and students study toxins affecting our food

I n his study of chemicals used to kill insects, weeds, rodents and other pests—Dr. Sayo Fakayode has come to call it: Pesticide on Your Plate. The slogan creates a terrifying mental picture, clearly outlining what’s become a worldwide problem.

He’s been researching this issue for more than two decades, recruiting undergraduate students and working with scholars worldwide to find quicker, cheaper and more accurate ways for detecting and analyzing pesticides in the human body.

His ultimate goal is to pave the way for a medicine that will help.

“I’ve said it repeatedly. Chemistry is chemistry anywhere in the world,” Fakayode said. “If you have the right skill set, and you are trained in analytical instrumentation—then what they do at Harvard or Yale or MIT or Georgia Tech—you can do right here on this campus.”

“At Georgia College,” he said, “we are making that little contribution to science.”

More than 1,000 different pesticides are used around the globe, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). They’re important for destroying vermin that eat or damage crops. But these toxins also make their way onto people’s plates. Nearly 75% of non-organic produce sold in the United States contains some amount of potentially harmful pesticides, according to the Environmental Working Group and reported by CNBC.

It’s not enough to wash pollutants off before cooking.

They’ve already been absorbed into the foods we eat.

These contaminants can cause health problems like birth defects, miscarriages and developmental disabilities in children, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

In addition, three chemicals used in making pesticides are considered “Group 1 carcinogens”— arsenic, ethylene oxide and lindane, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

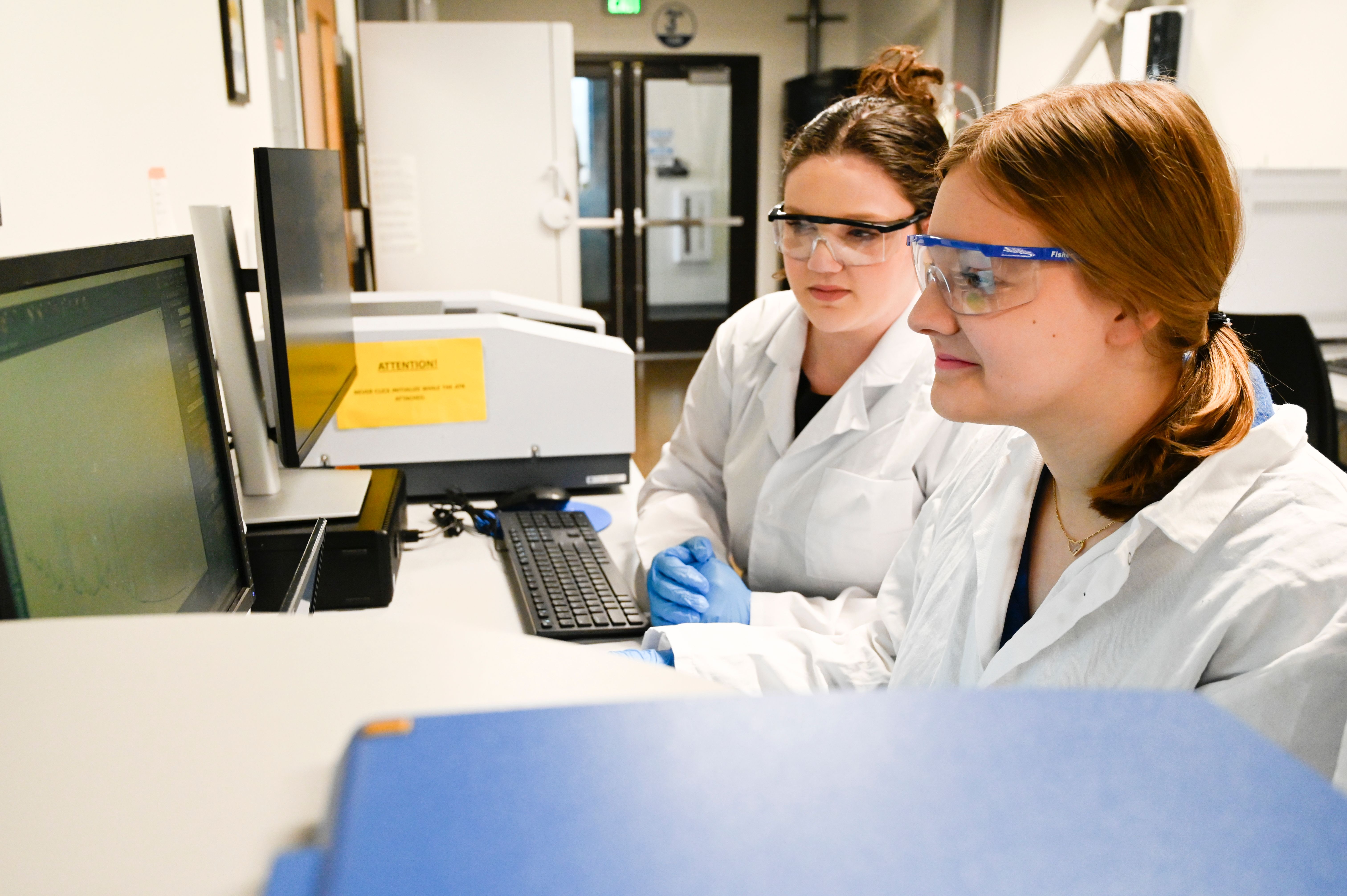

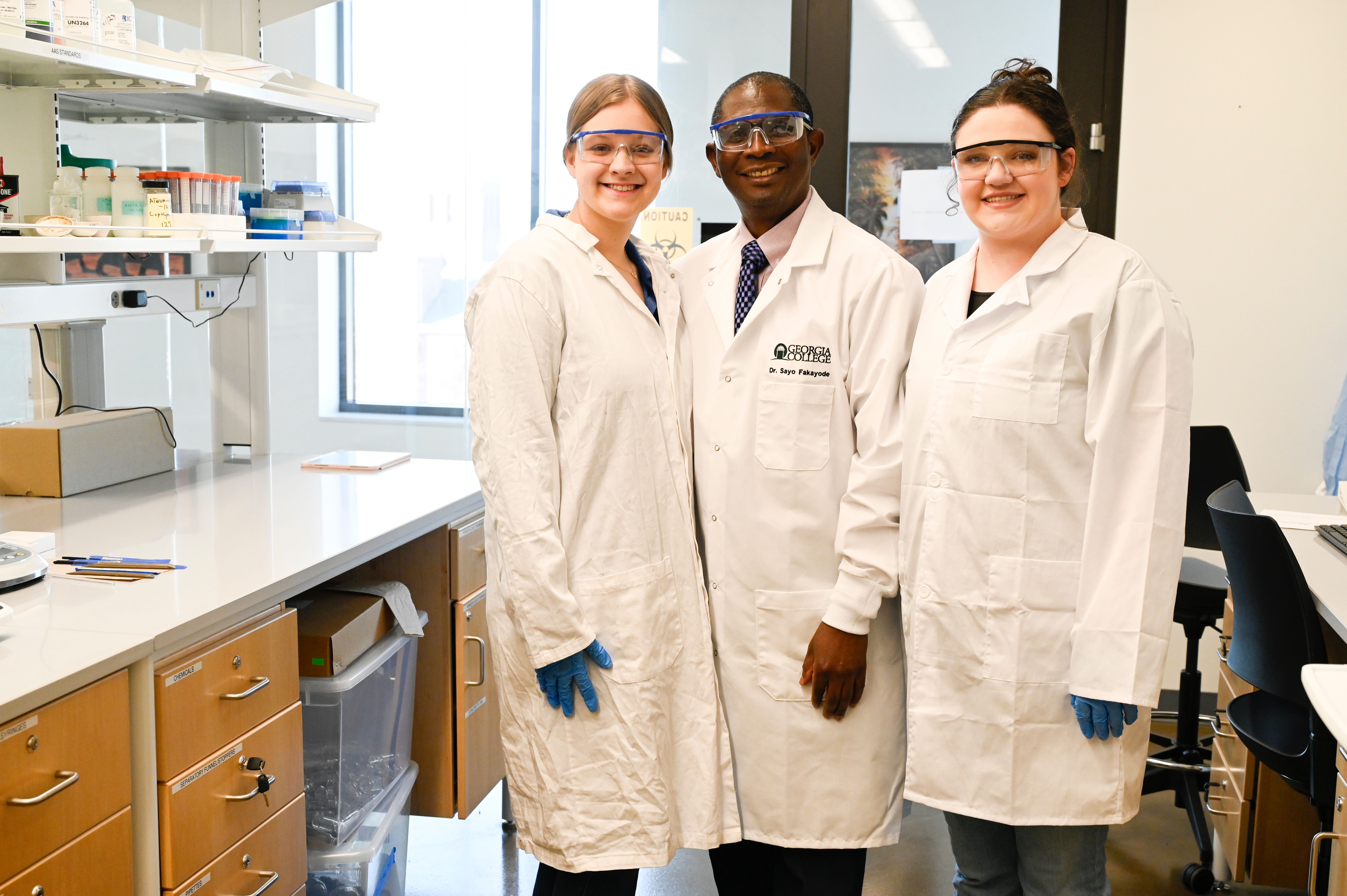

Rising senior Brinkley Bolton of Bremen, Georgia, and rising junior Bailey Dassow of Dacula, Georgia, are both majoring in chemistry with minors in criminal justice and concentrations in forensic science.

They were the youngest presenters recently at a research conference for the American Chemical Society in San Francisco, California. In January, they were also named as co-authors on a study with Fakayode and other university scholars in the Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics.

Finding a solution to the worldwide problem of pesticides is a “top priority,” the group concluded.

Seeing their names on an issue of global importance—alongside scientists like Fakayode and collaborating partners from Kennesaw State University in Georgia; Ball State University in Muncie, Indiana; and Red-Green Research in Bangladesh, India—was surprising.

“It’s a bit daunting to me, knowing we could have such an impact,” said Dassow, who began working with Fakayode freshman year.

Bolton agreed it’s “kind of crazy.”

“Not gonna lie,” she said. “I didn’t think I was going to be published at the age of 19 or 20. It’s weird. I’ve only been here three years, and I’ve already accomplished so much.”

“I didn’t think I could do this,” Bolton said. “I didn’t think I could do it until I was actually presenting research in California. Because it’s a small school, I’ve gotten so many more opportunities at Georgia College with research and being mentored by faculty like Dr. Fakay, than I could ever have gotten anywhere else.”

Dr. Eric Tenbus, dean of the College of Arts & Sciences, said he’s “extremely proud to have faculty and students of such high caliber contributing to the science of discovery here at GCSU.”

Fakayode also expressed pride in his “hardworking” students, who are part of the “creative thinkers and next generation of STEM researchers” produced in his department.

Dassow and Bolton helped Fakayode detect and analyze pesticides in the protein serum albumin. This protein is produced in the liver and enters the bloodstream, helping transport things like fatty acids, nutrients, vitamins and medicine to organs.

It can also transport bad things.

“This protein is not selective,” Fakayode said. “It will distribute toxins to various organs over time, accumulating pesticides and damaging tissues. If you look at deposits—you’ll see lipid fats. Pesticides are comfortable living inside fatty organs.”

Fakayode and his students wondered if they could develop better methods to evaluate how four widely-used pesticides interact with the serum albumin protein. To do this, they ran samples through Raman spectroscopy, a Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) instrument, mass spectrometer and molecular dynamic simulation.

These instruments compute data that allowed Fakayode and his team to detect changes as they occurred. The group accurately identified locations where the four pesticides bind with the protein.

The next step will be collaborating with other universities for animal tests. The endgame is developing a medicine to target and remove pesticides from proteins.

At Georgia College, Dassow will continue her work with Fakayode and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to develop a rapid, low-cost and accurate protocol for pesticide analysis in fruits, vegetables and dairy products. Bolton is currently researching polymers and plastics.

Bolton and Dassow are used to working weekends with Fakayode. One Friday night, they spent 11 hours finishing a samples analysis.

“It’s mind-boggling,” Dassow said. “I’m a sophomore, but I’ve already been published twice. It’s so much craziness. But I thrive on craziness and hard work. I learn so much more that way.”

Fakayode can be demanding, students said. But his high expectations help mold and ready them for the future. Research experience looks good on a resume and will put them a step ahead when applying for jobs.

“When I started Georgia College, older students would tell us, ‘You have to defend your research senior year,’” Bolton said. “And I was like, ‘OK, you’re kind of scaring me.’ But then I went to California and presented to people from all over the world. I was scared. You can ask anyone. I was very scared. I was like, ‘I don’t want to do this.’”

“But you know what?” she asked. “I did it. That’s what Dr. Fakay has given me—the confidence to show ‘I can do this.’”

Learn more about the Innovate Pillar in our Imagine 2030 Strategic Plan