Students learn overarching concepts on climate change through liberal arts perspective

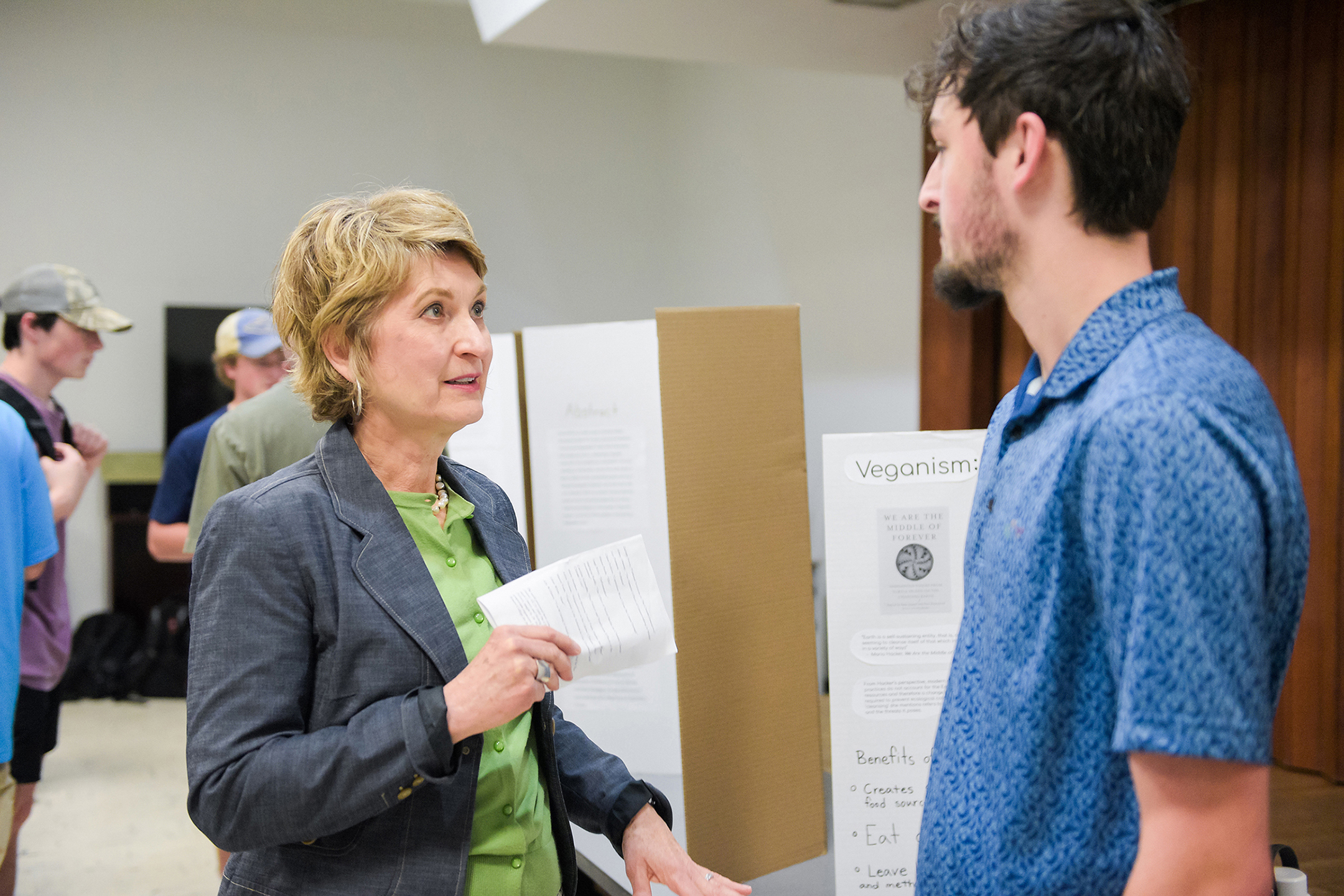

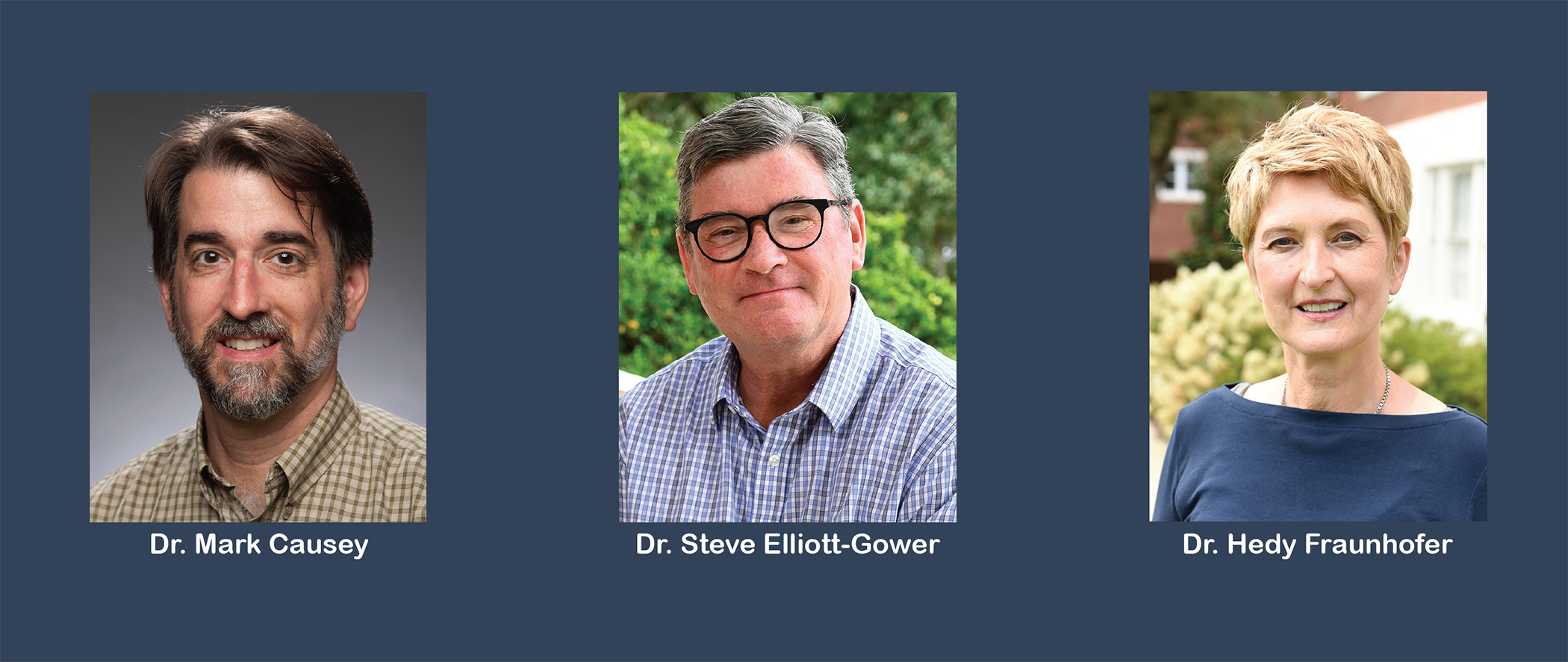

N ew, this past spring, students in the GC2Y 2000 Global Perspectives Class learned from expansive assessments on climate change. The class, taught by Dr. Mark Causey, senior lecturer of philosophy and religious studies; Dr. Steven Elliott-Gower, associate professor of political science; and Dr. Hedy Fraunhofer, professor of French and German, combined their teaching using the liberal arts approach.

Students learned about climate change from different disciplinary perspectives including the humanities, religion, philosophy, politics and policy. The faculty taught four sections to nearly 80 students. Elliott-Gower taught two sections of climate politics, while Causey and Fraunhofer taught two sections of climate emergency. Students then changed to new sections halfway through the semester.

“Students get a great example of a liberal arts education at its best, because we've got people from these various disciplines, addressing one central issue from different perspectives,” Causey said. “I hope that helps students connect climate change to the different classes they must take. What they learn in science class also applies in this humanities class and vice versa.”

The students formed multidisciplinary perspectives on climate change plus learned from industry experts. These included a business leader from Southern Alliance for Clean Energy and colleagues from the hard sciences like Dr. Hasitha Mahabaduge, associate professor of physics at Georgia College & State University. He laid a foundation for students by helping them understand a solar aspect of climate change.

“Even I learned why climate change, or global warming, can also cause cold spells that had been previously unseen,” Fraunhofer said.

“The complexity of the issue helped me understand that human beings are driving climate change,” Causey said. “It's going to require a fundamental shift in our thinking in our relationship to nature.”

“That's where the humanities—that often get left out of this discussion—come in and contribute,” Causey said.

“All students are shown climate change documentaries, that I wouldn't normally show in my class, to allow my students to see climate change from these other ethical and humanities perspectives,” Elliott-Gower said. “Also, bringing in industry experts is an enormously important part of what we're doing here.”

“Climate change touches on so many areas that to respond to something as big as this is going to require political, economic, scientific, ethical and religious responses. It touches every aspect of our lives,” Causey said.

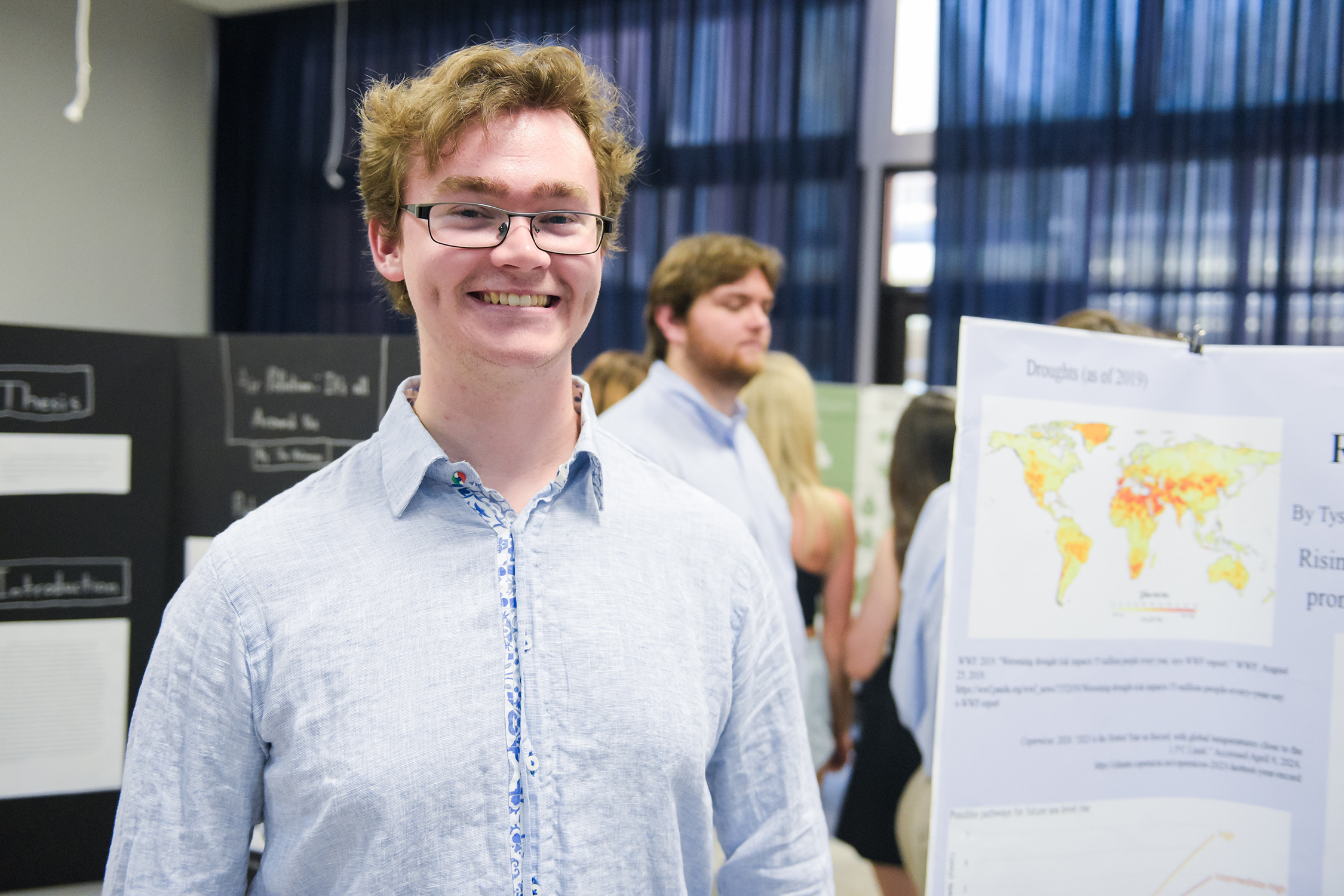

This class gave first-year accounting major Will Turner a look into the world’s larger problems that affect climate change.

“Taking classes with professors from diverse disciplines allowed me to consider different perspectives which expanded my own,” he said. “I don’t want to be narrow minded. Instead, I’d like to keep my mind open to new possibilities.”

All three faculty members also benefited from the multidisciplinary approach.

“I'm learning things about climate change that I didn't know before, and looking at climate change from these different perspectives that my colleagues in this multidisciplinary endeavor are bringing to my attention,” Elliott-Gower said.

“The pedagogical discussions we have among us are often on how to address this issue,” Fraunhofer said. “We're also learning how to teach from each other. That’s been helpful.”

“The science behind climate change has been in for several years now, and it's debatable whether we're reacting appropriately to the crisis,” Fraunhofer said. “The humanities have a significant role to play in facilitating this discussion.”

From the political perspective, students learn why progress on climate action is difficult because of competing political interests at stake from the corporate, oil and gas industries.

“International cooperation is especially difficult on climate change,” Elliott-Gower said. “This is due to massive ethical and equity issues that must be dealt with, namely, that we, in the Global North, are largely responsible for climate change. But it's primarily the countries in the Global South that experience the worst effects of climate change.”

“The industrialized nations, which happen to be the richer nations, caused the most damage,” Causey said. “The effects are mostly borne by poorer nations.”

“I highlight indigenous voices, as well, because indigenous people have already lived through colonization,” Causey said. “Their land—all of that’s already changed—it’s already gone. But they're still here.”

Several of his students commented that they’d never encountered indigenous voices and perspectives at the levels they’re studying in this class.

“It really gives them a different lens to think about what's going on,” Causey said. “That has proved helpful.”

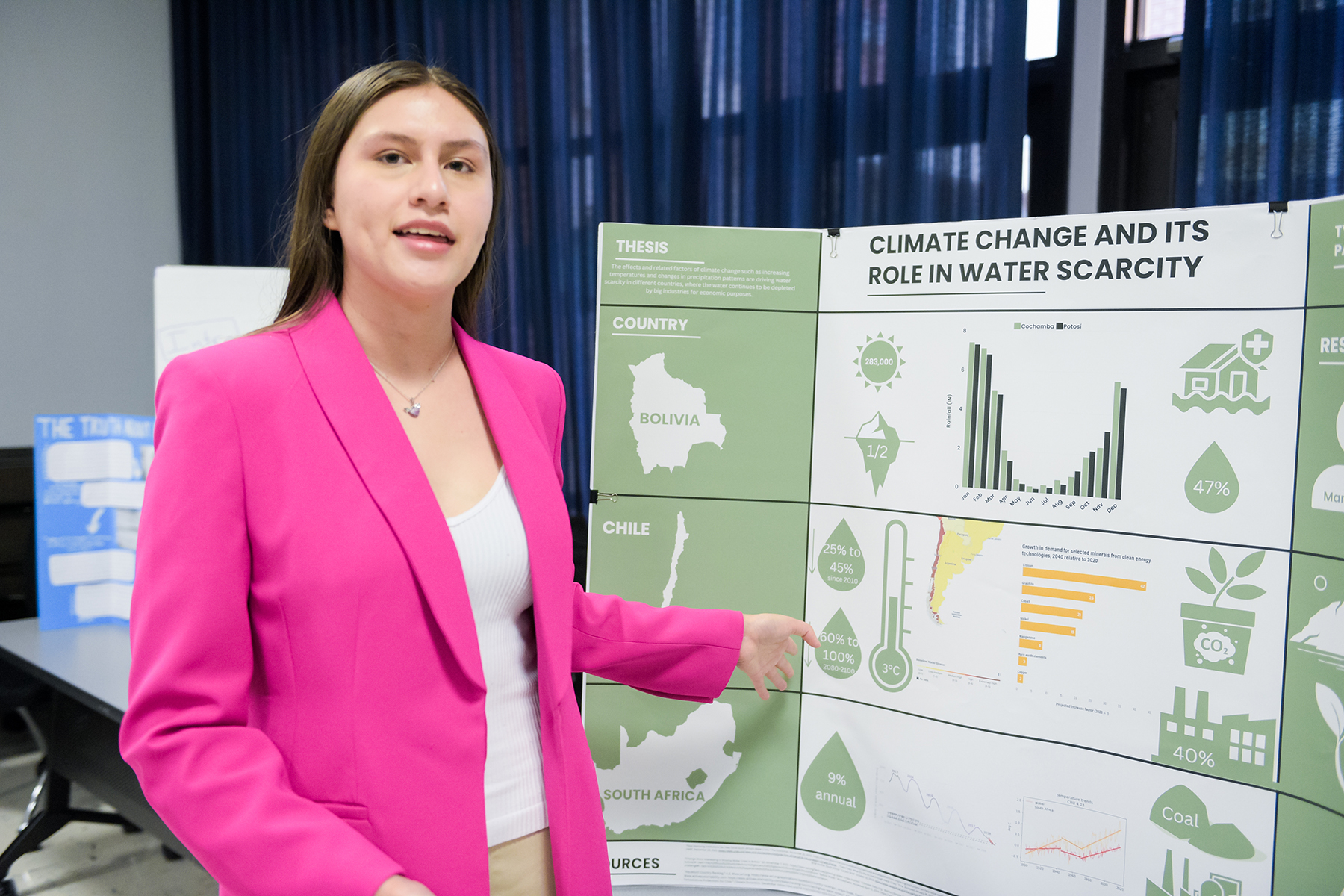

Since climate change is a global problem, Elliott-Gower points out the impacts of climate change in different countries, including the severity of effects near the equator. Then his class examines how these countries are responding.

“In the literature section, we read novels that feature the impact of climate change on different parts of the world,” Fraunhofer said. “Since I'm from Europe, I am very interested in news, including news about climate change, in Europe. So, I always draw cross-cultural comparisons on how different regions of the world are addressing or not addressing climate change.”

The effects of climate change are happening worldwide while disproportionately affecting people with the least ability to cope with those kinds of issues.

“Immigration into the U.S. is a big political issue,” Causey said. “But students don't realize how much immigration and migration around the world is caused now by climate change. These people are climate refugees. This problem is only going to get worse.”

“I hope our students leave these classes with a sense of hope, and more importantly, a sense of agency,” Elliott-Gower said. “They need to know there are things they can do both individually and collectively, to help us avoid the worst effects of climate change.”

Students learned that they’re part of the ecosystem.

“My hope is they leave with a broader understanding of our interconnectedness with nature—what we do to nature, we're doing to ourselves,” Causey said. “If we destabilize, we're undercutting our own ability to live and thrive. I hope this class gives students a feeling of connection with the larger world.”

Causey also hopes students will be informed voters when it comes to climate action.

Turner found this course to be “eye-opening” in learning about different ways countries across the world are responding to climate change. His area of focus was the European Union.

“The EU has a lot of power to reduce its emissions and the emissions of those who trade with it,” he said. “But countries like Kenya or Venezuela are focused on adapting to the impacts and trying to survive.”

Turner hopes to make the world a better place for everyone.

“I hope to gain the knowledge and skills necessary to continue holding corporations accountable for their emissions,” he said, “possibly by measuring the amounts and costs that should be applied to these emissions.”

Learn more about the Engage Pillar in our Imagine 2030 Strategic Plan